The Clapham Sect Connection

Why is it called "the Clapham Sect"?

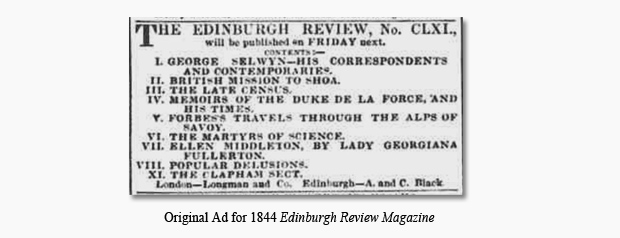

The Clapham Sect was not a club or organised group, as many scholars now imply. You were not granted membership or invited to join; you could not buy your way in; and no official membership list has ever existed. In fact, those involved never distinguished their fellowship by this (or any other) name. In an 1844 interview, Sir James Stephen inadvertently referred to the group of reformers as "the Clapham sect". The editor of the Edinburgh Review liked the phrase and used it as the title of the article. The name stuck.

Who were the "members" of the Clapham Sect?

Without debate, William Wilberforce was the head, or leader, of the group of reformers. While, as aforementioned, there were no members (simply because there was no club), modern researchers now require that two qualifications must be met for a person to be considered as having once belonged to "the Clapham Sect". Firstly, friendship with Wilberforce is essential, including a most-emphatic sharing of his staunch Christian motives for reform work. Secondly, and just as essential, was active engagement in one or more of the political or social reforms with which Wilberforce was involved. Wilberforce had many friends who were not part of the group, just as there were scores of political and social reformers who do not qualify. For example, William Pitt the younger, Wilberforce's closest friend, was not part of the Clapham Sect. While he certainly meets the second qualification, and his friendship with Wilberforce is unequivocally recognized, his lack of Christian motivation for reform keeps his name off the lists.

What mission(s) unified this group of reformers?

The Clapham Sect's most important and well-remembered achievement is, undeniably, the Abolition of the Slave Trade (culminating in the Abolition of Slavery throughout the British Empire). The impressive list of their other political and social reforms, however, although relegated to obscurity, should not be lost in the shadow of the great. These exemplary Christian men and women spent their lives working for the greater good, such as "the protection of Sunday", prison reform, and basic Parliamentary reform. They also founded schools, missions, and groups (such as the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals). While individuals in the Clapham sect may have only been involved in one of the many Christian reform activities, each person's ubiquitous support for all served to edify the whole.

Where did the Clapham Sect reformers actually live?

This aspect is often debated in books and articles, and there is, of course, no absolute answer. Some think that only the friends who actually resided in Clapham can be considered for inclusion in the roll call, but I respectfully disagree with this approach. I believe that the name, "the Clapham Sect", identifies (and unifies in the mind) a group of individual reformers who were motivated by their personal faith in Christ to accomplish works that would enable the spread of the Gospel and the making of a better world. Stephen Tomkins argues in his book, The Clapham Sect,* that Thomas Clarkson and Granville Sharp should not be included in the list. He states that they were collaborators with the Clapham Sect in the group's most important campaigns, the fight against slavery and the founding of the Sierra Leone company, but that the two men were not "spiritual brothers". This is only true if you confine the group to people who held to the doctrines of what was termed "Evangelical Christianity". If this were true, Wilberforce (who held to no particular denomination) would have to be excluded from the list. As one united body in the work of Christ, the individual reformers would not have considered that their manner of worship or obedience to God would make them more or less of a Christian than the others. Since there is no doubt that Clarkson and Sharp were motivated by their own Christian faith, I believe that they should be included in the "cast of characters".

When was Edward James Eliot active within the Clapham Sect?

Through university years and post-school travel, Eliot, Wilberforce, and Pitt were the closest of friends. From the earliest social-reform days, Eliot was supporting Wilberforce (e.g., the founding of the Association for the Discouragement of Vice in 1787). In 1792, Henry Thornton invited Wilberforce to come and live at his Clapham house, Battersea Rise. They called it a chummery, each man paying a share of the housekeeping. That same year, Thornton built two houses, one on each side of Battersea Rise: Glenelg, purchased by Charles Grant (member of the Clapham Sect and Chairman of the Board of Directors for the East India Company), and Broomfield, rented to Edward James Eliot.

Eliot was a director of the Sierra Leone Company. He was active throughout his entire Parliamentary career in the effort to remove bribery from elections and was credited with the downfall of Succession-by-Purchase to Exchequer Clerkships. He was lead supporter of Joseph Hadrcastle's efforts to reform the East India Company, a member of a group attempting to reform the Marylebone Workhouse, and a founder of the Society for Bettering the Condition of the Poor. Eliot held the position of Joint Commissioner for Indian Affairs, and Wilberforce and others pressed for his nomination as Governor-General of India. Their plan was simple – if they could succeed in establishing a Christian Governor-General, Wilberforce and his friends would be able to open the country to Christian missionaries and Bible distribution. (Unfortunately, due to his failing health, Eliot was forced to decline this position.)

The Death of Edward James Eliot

39-year-old Eliot died in September 1797, leaving others to complete the work begun by the small circle of friends. While his name is, for the most part, forgotten in the annals of history, Eliot was the "bond of connection, which was sure never to fail," between Wilberforce and Pitt. With the loss of Eliot, this bond did fail, and the two great reformers lost their direct line of communication to each other.

After Eliot's death, William Wilberforce wrote to Hannah More:

Except Henry Thornton, there is no one living with whom I was so much in the habit of consulting, and whose death so breaks in with all my plans in all directions. We were engaged in a multitude of pursuits together . . .

Pitt's reaction to this saddest of news was described in a letter to Wilberforce by George Rose, Pitt's secretary and friend:

The effect produced on Mr. Pitt was, as you may imagine, beyond description; it has not happened to me to be a witness of such a one, as I saw him immediately after his getting Lord Eliot's letter [informing Pitt of Edward James' death] by the common post, and reading it among others, not knowing the writing; it is difficult even to conceive the impression made by the misfortune, and the manner of hearing of it. To say that from the bottom of my heart I lament the loss, is poorly expressing what I feel; I can say truly that in my intercourse with men I have met with few, very few indeed, such as our poor friend was.

The entire Clapham Sect was deeply saddened by Eliot's death, though they all recognized that he had gone to a "far better place". Their feelings are, perhaps, expressed best by Charles Grant, in a letter to Wilberforce (written on 23 Sep 1797, three days after the news of Eliot's death reached London):

"Now that he is gone, I feel for him with all the sentiments of true friendship; and I feel for the public and the church. There being but few such characters, his removal is both a misfortune and a dark omen."

*Tomkins' book, The Clapham Sect, should be obligatory reading for anyone interested in this movement. I highly recommend it on the basis of the three-and-a-half-page "Cast of Characters" alone. The concise and informative text is, in my opinion, a lovely bonus!